As part of ‘Exist, Resist, Return’: A Week of Action for Nakba Day, called for by Publishers for Palestine we are making some content by Palestinian writers freely available on our website.

– by Lara Khaldi

The museum in resistance is not as we imagine: a material structure and archive of a past struggle of emancipation. It is rather the generative collective disintegration of this material in the struggle for forging collective myths. The museum in resistance is a museum outside of time, as time is always controlled by the hegemonic power. It is a museum which does not reserve a record nor a trace, but rather a shared knowledge in continuous circulation and transformation.

Take One: The Museum Object in Battle

In her essay A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War,Hito Steyerl writes about a military tank that was stolen from the pedestal of a WWII monument in Ukraine and used in battle during the 2014 conflict.[2] Borrowing from Giorgio Agamben’s work on the relationship between civil war and stasis, Steyerl accuses the museum of being the site – perhaps even the engine – of a history which keeps returning and remains stuck in a loop. She defines the kind of history that returns by the re-use of the tank as ‘partial, partisan, and privatized, a self-interested enterprise, a means to feel entitled, an objective obstacle to coexistence, and a temporal fog detaining people in the stranglehold of imaginary origins.’[3] In other words, the exhibition of the tank on a memorial site is complicit with this history, as it embodies it, makes it available and visible, causing its return. Following her argument, the museum functions as a time travel machine that hurls us back into loops of violence: ‘[t]he museum leaks the past into the present, and history becomes severely corrupted and limited.’[4] National museums work under the assumption that its objects are representative of its citizens, tacitly equal and homogeneous. However, this only continues to aggravate residual tensions. Civil Wars thrive on historical tensions and are usually propelled by national, ethnic or religious binaries, which mask class struggle and injustice caused by the ruling national bourgeoisie.[5] Still, museums present themselves as public institutions and the objects within them as owned by the citizens of the state. Exhibitions in this sense become a means for the representation of the nation. Thus, it is not illogical for citizens to re-use its objects. Once the objects are exposed and re-used, the museum’s time seeps out of its doors, infecting all its citizens, trapping them into a loop.

The birth of the modernist museum has always been associated with revolution, with the Louvre as the emblem of this history. If the museum is post-revolutionary, it is also postcolonial, as it is often one of the first institutions to be built post-independence. In the Palestinian context however, time outside the museum is still under settler colonialism, and resistance to this is still underway. So, while the debate around decolonising the museum is rooted in a ‘postcolonial time’, the colonialization of Palestine continues, and the struggle against it ensues as an elongated present. We therefore find ourselves in an uncanny situation where we suffer the symptoms of a new post-independence nation state, with new national museums, local authorities, and a neoliberal economy, while still under settler colonial rule and without sovereignty over land, people or infrastructure. Considering this asynchronicity with the temporal rhythms of the national and modernist post-revolutionary museum, what happens to the objects within them, and how do they remain active in the present?

Take Two: Fugitive Objects

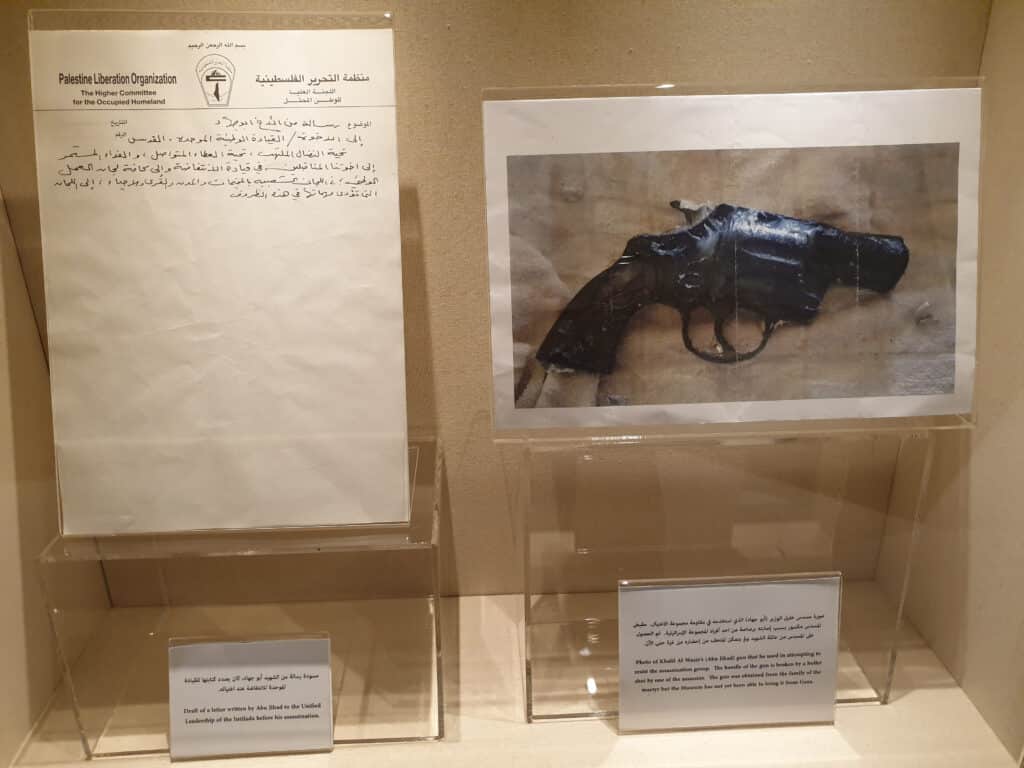

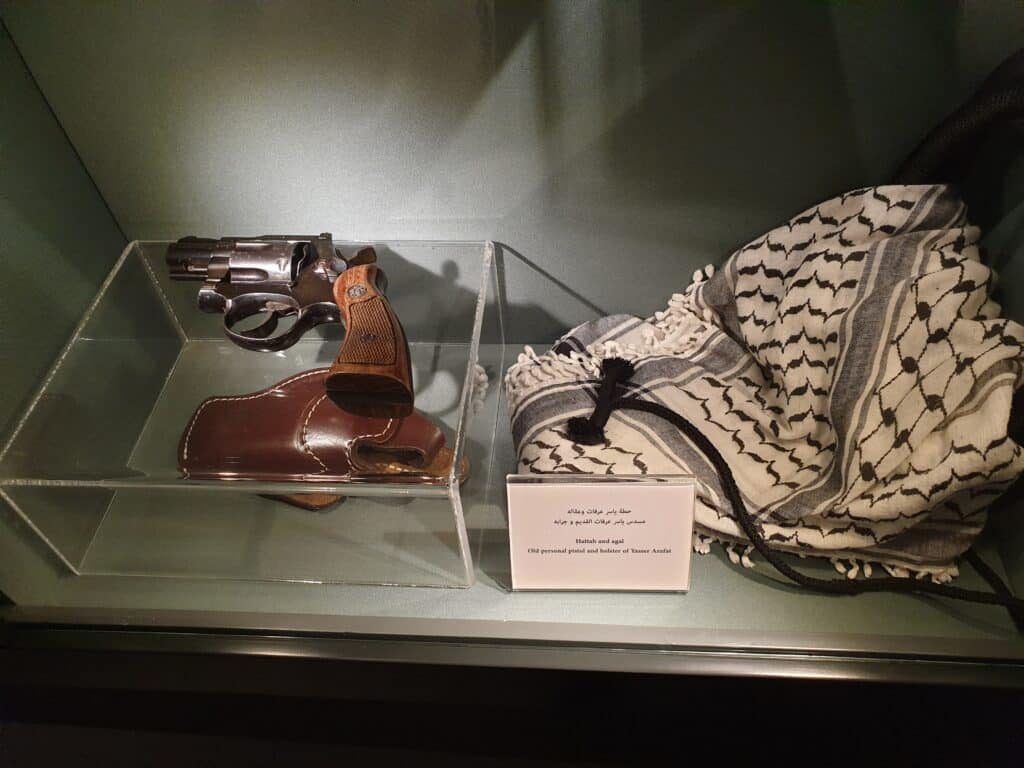

The Yasser Arafat Museum in Ramallah exhibits a number of weapons, some with a symbolic provenance. One such weapon is the personal pistol of the late Yasser Arafat. Another gun belonged to the late Khalil Al Wazir (Abu Jihad), co-founder of the Palestine Liberation Organization and commander of the armed wing of Fatah.[6] Yet there is a stark difference in the ways the two pistols are exhibited. While the pistol of Arafat is displayed behind museum glass, near the famous speech he gave at the 1974 UN General Assembly, Abu Jihad’s is only represented by a photograph. Arafat’s pistol has had a symbolic function ever since he spoke the most famous lines from his 1974 speech: ‘Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom-fighter’s gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.’[7] Almost fifty years later, encased in museum glass in Ramallah, the pistol is evidence of the death of that revolutionary era for the leadership. It represents the trigger for the museum’s present day politics; their collaboration with settler colonial powers through censorship, repression and security coordination.

The picture of Abu Jihad’s pistol on the other hand, is like a hole in the museum. From this crack, present day reality seeps in. Underneath the photo, the label reads: ‘The gun was obtained from the family of the martyr but the museum has not yet been able to bring it from Gaza.’ Abu Jihad was assassinated in 1988 in Tunis by the Mossad. The pistol carries traces of the assassination, as the handle is shot off. The reason why the museum cannot physically obtain the pistol is because it is impossible for his widow to transport it through Erez, one of the Israeli checkpoints encasing Gaza in an impenetrable siege for over ten years.[8]

Every time I visit the Yasser Arafat Museum, I wonder why the photo of Abu Jihad’s pistol is exhibited, since the museum is an obvious site for claiming the death of a revolutionary era and setting the stage for the narrative of the present political regime: peaceful negotiations, security coordination and political complicity with the Israeli settler colonial regime. The photo of Jihad’s weapon posits an opposing narrative of the museum. Naturally, we all know that the museum (and any other conduit for hegemonic ideology for that matter) is not omniscient and that it leaks, breaks and falters. However, this looks like a very deliberate curatorial decision. A photo of the pistol behind museum glass. I would postulate that it is an attempt at de-functionalising the pistol even while it is outside the museum. The museum would like to capture both militant past and present and put them to their death, thus, it situates resistance to settler colonialism in the past in an attempt to frame everything in a postcolonial time. The photograph of the pistol, therefore, carries within it the contradiction and tension within this museum.

However, contrary to the desire of the museum, the photo of the pistol has invoked various stories, rumours and myths as to why the pistol is missing. In fact, the photo looks like a wanted poster. The museum wishes to capture the fugitive pistol, but as sometimes happens with wanted posters, its purpose backfires, transforming the outlaw into a popular figure of rebellion. In The Undercommons, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten write of the fugitive as the outlaw, as the rebel, the one who stands their ground against the settlers.[9] Evading the relationship between the powerful and powerless, the fugitive is rather the one who transgresses this relationship of binaries by refusing ‘to be corrected.’[10] Similarly, some objects are compelled by colonial powers to refuse to enter the museum, to refuse to be transformed into pure postcolonial form, into corpses of colonial time.

Take Three: The Museum Before or After the Revolution?

As stated above, the Louvre is considered by many to mark the birth of the modern museum. The conversion of the palace into a museum was propelled by the French Revolution. As discussed by Boris Groys, the decision by the revolutionaries whether to destroy the palace or not was resolved by converting it into a museum, an iconoclastic response which turns everything in the museum into material evidence of the death of the past regime/s.[11] This irrevocable death marks a new political era outside the museum, de-functionalising its objects, transforming them into art.[12] So, the museum’s time, according to Groys, is after the end of a revolution. The museum in this way functions to deem not only what is inside of it irrevocably dead but also the revolution itself. Revolutions are defined by the present, as they are usually the moment of destruction of the present regime. Once this regime is destroyed, the revolution is destroyed along with it. Museums are built to commemorate those revolutions; they become both evidence of the death of a past regime and guarantor that another revolution is unnecessary. This is precisely the case with the Yasser Arafat Museum; it commemorates the history of the militant era, or what Palestinians refer to as the Palestinian Revolution, subsequently hurling it into the past. With the post-revolutionary museum in place, there is no longer a reason to revolt. Time in the modernist museum moves between history and the future. The present is only a tunnel. History is employed to determine the future, and the future is rather posited as the present.

Take Four: The Secret

There is another notorious gun in the Palestinian imagination. During the – continuing – Nakba of 1948, many Palestinians buried their valuable belongings (ranging from photos to gold) in their backyards or secret locations, so they would be able to retrieve them once they returned, not knowing that many of these belongings would remain buried for decades. However, the stories of those underground remainders keep circulating in the diaspora and across generations. The satirical novel The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist by Emile Habibi, tells of is such a story. The novel centres around the strange time of the Nakba aftermath. Chronicling the struggles and transformations of the anti-hero, Saeed, and his family, the story spans two generations, wherein his son is empowered by the buried objects. Two secrets haunt the novel: the first is that Saeed is a collaborator with the new regime, and the second is a buried treasure box that his wife’s family hid in a cave in their village, Tantoura, before they were forcibly expelled in 1948. Eventually, their son finds the treasure box, which contains guns and gold, and becomes a Fida’i (resistance fighter).

The Nakba of 1948 defined the Palestinians as a collective through the shared experience of death and expulsion. The moment of death and burial is simultaneously the moment of birth and reproduction.[13] Therefore, the novel’s return to the buried treasure follows this form of movement. Throughout the novel, the buried treasure functions like a promise of salvation, a reminder of a possible return, the potential for some kind of emancipation. Indeed, the story of the treasure box enables the son to become a resistance fighter. The act of burial produces life; the stories of the buried objects circulate among the Palestinians, they are kept alive through continuous oral chronicling.

Take Five: What About the Present?

In All Shall be Unicorns, Marina Vishmidt writes about the notion of the commons and art activism in relation to time. She juxtaposes communist time with commonist time. Vishmidt argues that the fulfilment of communism takes place after the revolution; thus, it exists in the future while commonist time takes place in the present. Commonism is rooted in the present because, instead of waiting for the future revolution or political mobilisation against the state, or making demands of the state, it launches its affirmative projects in the here and now. In the modernist conception of time, and its association with progress, the present and the future become binaries, as we resist the present and work towards a ‘better’ future. According to Vishmidt, the commons is still ‘future oriented’ but embodied rather than using time as a medium for its realisation. The commons ‘does not oppose the present, but proposes an active reconstruction of it from within.’[14] Moreover, this idea of progress, which sees the present as the tunnel for the future, is at the very core of capitalism, as financial markets are based on future projections and speculation. Postponement and delay are tactics of the market and a means to control the present. According to Timothy Mitchell, even the construction of infrastructure is built to delay and accumulate interest and profit.[15] However, the future orientation of the solution to come is futile in the case of settler colonialism. For the oppressed, the present and the everyday are determined by struggle and resistance. Thus, a deferral into the future constitutes self-denial.[16]

Practices of the commons are also rooted in the everyday. Capitalism pervades every aspect of our lives; its violence is slow. Vishmidt discusses the different discourses of the left around the fight with capitalism, and a futurist orientation seems to pervade. Those discourses are set after the destruction of capitalist institutions opens the way for communist living. Commonism is instead situated in the present and is rather affirmative, building communities and support structures which are based on alternative economies, slowly and silently leaving those hegemonic institutions to falter and fall. So, is the time of the museum in resistance the present?

The museum in struggle needs to be a site of burials. As Groys writes, contrary to the prevalent narrative of calling the museum a graveyard, the graveyard is a space full of possibilities.[17] Stories about graveyards abound. Death in the graveyard becomes generative. Spirits inhabit the present. In popular culture, there are many stories about corpses awakening at graveyards, less so at museums.[18] The secret and promise of finding the treasure box in The Pessoptimist functions in the same way. The buried treasure box reminds the son of his mother’s village and the necessity for return. Similar to Abu Jihad’s missing pistol, the story of the object and its emancipatory powers survives because of its lack of exposure.

Take Six: Archives in Resistance

The museum of resistance is a museum engaged in struggle. Therefore, it is a museum outside of time. During the first intifada in Palestine, underground communiqués were discarded by burial; they were deemed illegal by the Israeli military, and any Palestinian caught reading or in possession of one was arrested. So, the communiqués had to disappear after they were read. Burning was not an option since the traces are incriminating, so it is said that they were dumped in wet concrete construction sites or buried underground. The future material exposure of these documents implicated their readers and authors. This is precisely the danger of the exhibition of a material archive during a struggle. Any record is incriminating. To be outside of time is to be outside the reaches of the archive and surveillance. It is through the collective practice of struggle and resistance that a community can attempt to be outside of time. It is through preserving a secret together.

The late eighties in Palestine were distinguished by collective emancipatory knowledge production and radical imagination. Another form of an archive in resistance is a book named Falsafat al Muwajahah Wara al Qudban or The Philosophy of Confrontation Behind Bars. This book was smuggled in fragments inside of capsules by political prisoners and circulated outside and inside of Israeli prisons to educate Palestinians about how to confront political imprisonment. The book does not contain any publishing information; neither the author, the publication date, nor printing information are mentioned. Scholar Esmail Nashif writes about the deliberate absence of this information:

The main characteristic of the space/time of the no-naming practice is the fact of being out of reach of the colonizer’s surveillance practices. But in the case of Philosophy of the Confrontation Behind Bars this being out of reach is not a passive fragile insulation. On the contrary, the invisibility is capitalized on to resist the colonizer whose eye is blinded by the secrecy. The act of no-naming blinds the colonizer’s eye/discourse.[19]

The absence of the information places the book outside of a record of time and space which the coloniser controls. To achieve this resistance to the time and space of the coloniser, authorship should encompass the collective: ‘The author is the collectivity… By not naming it, one reproduces the myth of the We.’[20] The record of knowledge by the Palestinian collective body was materialised and circulated because it was necessary to share in and for resistance. However, the way it was disseminated protected the collective instead of exposing it. The absence of a date places this body of knowledge outside of time, making it impossible to capture yet available to everyone. The underground authorship and circulation of collective knowledge is one of the aspects of a museum in resistance. The medium of this museum is continuous collective dissemination rather than a building made of concrete with an immovable collection about resistance.

Top image: Jumana Emil Abboud (@jumanasan), Ein el-Joz Bride, 2015. Gouache and pastel on paper, 28 x 39 cm. Photo by Issa Freij

[1] The title of this text inspired by the poem ‘The Exiles Don’t Look Back’ by Maḥmūd Darwīsh In: Darwīsh, Maḥmūd. Now, As You Awaken. Transl. Omnia Amin and Rick London. San Francisco: Sardines Press, 2006.

[2] Steyerl, Hito. ‘A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War’ e-flux. February 2016. <www.e-flux.com/journal/70/60543/a-tank-on-a-pedestal-museums-in-an-age-of-planetary-civil-war/>.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Amel, Mahdi. ‘Al Thaqafa Wal Thawra.’ Al Hiwar Al Mutamadden, Al Hiwar Al Mutamadden. 23 May 2016. <www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=518075>.

[6] Afbeeldingen pistolen

[7] Arafat, Yasser. ‘Yasser Arafat’s 1974 UN General Assembly speech.’ United Nations General Assembly, New York. 13 November 1974.

[8] In the larger context of the PA the Palestinian police cannot even move with their weapons between different zones and ghettos, as connecting roads are under Israeli control.

[9] Harney, Stefano, Fred Moten. The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning & Black Study. New York etc: Minor Compositions, 2013.

[10] Ibid.: p. 1.

[11] Groys, Boris. ‘On art activism’ e-flux journal, no. 56 (2014): p. 1-14.

[12] Groys even suggests that it is the modernist museum which marks the transformation of design into art

[13] Nashif, Esmail. Images of a Palestinian’s Death. Beirut: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2015.

[14] Vishmidt, Marina. ‘All Shall Be Unicorns: About Commons, Aesthetics and Time’ Open! Platform for Culture, Art & The Public Domain. 3 September 2014. <www.onlineopen.org/download.php?id=128>.

[15] Mitchell, Timothy. ‘Infrastructures Work on Time’ e-flux architecture. 28 Jan. 2020. <www.e-flux.com/architecture/new-silk-roads/312596/infrastructures-work-on-time/>.

[16] Joseph Massad uses the term postcolonial colony to describe Palestine with which he presents a historical argument where Zionism presents Israel as a postcolony. In: Massad, Joseph A. The Persistence of the Palestinian Question. Essays on Zionism and the Palestinians. New York etc.: Routledge, 2006.

[17] Groys 2014 (see note 10)

[18] Ibid.

[19] Nashif, Esmail. Palestinian Political Prisoners: Identity and Community. New York etc.: Routledge, 2008.

[20] Ibid.